Protecting The North Atlantic during WWII with Tom Hanks & his destroyer(s)

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

During WWII and for at least a decade thereafter, there were dozens of movies set aboard a submarine or destroyer—often featuring both as adversaries. Since then, 1981’s Das Boot is definitely the most celebrated U-boat film. Now comes Greyhound, a fact-based, above average WWII adventure pitting a destroyer vs a sub.

Based on C. S. Forester’s book, The Good Shepherd, Greyhound centers on the USS Keeling, a Fletcher-class destroyer (with radio call sign “Greyhound”), helmed by Commander Ernest Krause (Tom Hanks) of the U. S. Navy. Greyhound is one of four destroyers charged to escort and protect 37 Allied troop and supply ships heading to Liverpool. Commander Krause is also in charge of the other escort ships, even though this is his first wartime command. He accepts the challenge with humility, respect, and his Christian faith. (He often quotes scripture.)

It is a fine performance which Hanks effectively underplays. Note that Hanks also wrote the screenplay adaptation. Aaron Schneider (Two Soldiers; Get Low) directed.

It is a fine performance which Hanks effectively underplays. Note that Hanks also wrote the screenplay adaptation. Aaron Schneider (Two Soldiers; Get Low) directed.

The unique visualization is credited to cinematographer Shelly Johnson, whose rather tricky balancing is realized by editors Mark Czyzewski and Sidney Wolinsky. By that I mean the obviously digitalized rough Atlantic waters with the convoy ships have to seamlessly blend with Krause and his crew onboard the Greyhound.  Critics have complained of the computer game look, but it works well. The far away overview of grim sky just adds to the flint-gray look of ships amongst churning sea water.

Critics have complained of the computer game look, but it works well. The far away overview of grim sky just adds to the flint-gray look of ships amongst churning sea water.

When the convoy enters the “Black Pit,” unprotected waters minus any air support, the film’s action ensues. It becomes the escorts versus the wolfpack of German submarines—seven of them. It is the proverbial cat and mouse game: depth charges, torpedoes, maintaining silence to avoid Sonar, heavy artillery, and widespread  destruction. We have seen this before in naval war flicks, but Greyhound is an exception. We get to know the Greyhound’s officers and men. However, we never see anyone connected to the submarines.

destruction. We have seen this before in naval war flicks, but Greyhound is an exception. We get to know the Greyhound’s officers and men. However, we never see anyone connected to the submarines.

Greyhound is a single-viewpoint tale. I kept thinking of 1957’s classic Robert Mitchum/Curt Jürgens destroyer/submarine film, The Enemy Below, wherein there is a juxtaposition of the American and German captains and crews. The two captains even meet face-to-face at the end!

Featured in the Greyhound cast are Stephen Graham as Krause’s Executive Officer, and Rob Morgan as the Mess Attendant. Elisabeth Shue is briefly shown in a couple of flashback sequences, portraying Krause’s love interest back home.

Featured in the Greyhound cast are Stephen Graham as Krause’s Executive Officer, and Rob Morgan as the Mess Attendant. Elisabeth Shue is briefly shown in a couple of flashback sequences, portraying Krause’s love interest back home.

Running a tight 91 minutes, Greyhound is a tense, nearly non-stop actioner.

∞∞∞∞∞

GRADE on an A-F Scale: B

Richard Boone, ‘Knight Without Armor,’ gets story told in new book

(NOTE: The following book review was originally published in The Kansas City Kansan on July 14, 2000.)

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

Richard Boone will forever be Paladin, like it or not. Boone’s western anti-hero was the central character in the long-running TV hit, Have Gun – Will Travel. And for many reasons, the actor did not like it. It is the same old, same old Hollywood story of typecasting. Some learn to live with losing other acting jobs because of being identified with a singular role. Some, like the late Boone, turn to booze and brooding.

At last, someone has written what strives to be the definitive story of the very private Richard Boone, the stage actor who played support in a dozen Hollywood films before being given a starring post in his first TV hit, a doctor show no less; and finally hiding out Tinseltown West to to find his greatest successes as cowboys Paladin and the dubious Hec Ramsey.

Author David Rothel also covers Boone’s impressive but doomed-from-the-start anthology series, The Richard Boone Show. Despite an irritating narrative style, actually non-style, Rothel’s 274-page hardcover, Richard Boone—A Knight Without Armor in a Savage Land ($35, Empire Publishing, Inc.) is an easy and fascinating read.

As a long time fan of Boone, I was hungry to discover anything about the man. This is a guy who made 25 pictures and starred in four TV series, and yet this is the first book to chronicle his life and career. (Boone died in 1981.) Try to find magazine or newspaper articles about Boone—even during his time. Sparse. Considering that most people of at least middle age have very fond, even touching, memories of Boone and his work, the publishing of this book constitutes a shameful afterthought.

As a long time fan of Boone, I was hungry to discover anything about the man. This is a guy who made 25 pictures and starred in four TV series, and yet this is the first book to chronicle his life and career. (Boone died in 1981.) Try to find magazine or newspaper articles about Boone—even during his time. Sparse. Considering that most people of at least middle age have very fond, even touching, memories of Boone and his work, the publishing of this book constitutes a shameful afterthought.

Rothel, a full-time language arts teacher, uses the same format he has utilized in 11 books covering the celluloid Western gamut. From his The Gene Autry Book to An Ambush of Ghosts, a Personal Guide to Favorite Western Film Locations, Rothel fills his books with segmented interviews about the particular book’s subject. The interviews are presented the easiest way possible, strictly as Q & A reads, and that simplistic style has its drawbacks. It certainly makes for fast scans in short doses. For example, one of the book’s highlights is the 8-page Johnny Western interview. Western, who performs about once a year in  Kansas City and has a daily radio show in Wichita, also wrote and sang the Paladin theme with lyrics, “Have Gun – Will Travel reads the card of the man, a knight without armor in a savage land….”

Kansas City and has a daily radio show in Wichita, also wrote and sang the Paladin theme with lyrics, “Have Gun – Will Travel reads the card of the man, a knight without armor in a savage land….”

Talk about typecasting. No surprise that Western cannot get off any stage without singing this signature. But would you believe that he came close to not getting to perform it on air? Columbia Records producer, Mitch Miller (before his Sing Along TV series) had other ideas.

“Before we were ready to record,” Western recalls, “Mitch  thought about Jerry Vale, who was under contract to Columbia and hadn’t had a hit for years and years.”

thought about Jerry Vale, who was under contract to Columbia and hadn’t had a hit for years and years.”

When Western told Boone about Miller’s plan, Boone immediately got on the phone to New York and reasoned with the producer.

“Listen, you son of a bitch,” blasted Boone, “the kid is going to sing the song and that’s all there is to it!” Western recounts a pregnant pause with Boone finally saying, “I knew you’d see it my way, Mitch.”

“Dick (Boone) just kicked the doors open for me,” said Western, “and I owed him forever and ever and ever.”

Co-stars, stunt men, producers, directors, and relatives (including Boone’s son Peter) recall Boone’s friendship, humor and theatrical brilliance as well as his raucous boozing

and mood swings that eventually contributed to his ill health and death at age 63. The book also includes a detailed chronology of all Boone’s films and TV work, including his four series, beginning with Medic (1954-56), Have Gun-Will Travel (1957-63), featuring Boone as the man in black who supported his luxurious San Francisco lifestyle by hiring out as a gunfighter. Ratings-wise, it could have gone much longer, but Boone edged out to begin his soon failed anthology series, The Richard Boone Show (1963-64). Hec Ramsey followed in 1972 with a two-year run.

and mood swings that eventually contributed to his ill health and death at age 63. The book also includes a detailed chronology of all Boone’s films and TV work, including his four series, beginning with Medic (1954-56), Have Gun-Will Travel (1957-63), featuring Boone as the man in black who supported his luxurious San Francisco lifestyle by hiring out as a gunfighter. Ratings-wise, it could have gone much longer, but Boone edged out to begin his soon failed anthology series, The Richard Boone Show (1963-64). Hec Ramsey followed in 1972 with a two-year run.

Loaded with showbiz nuggets like the fact that Boone was originally asked to star in Hawaii 5-0, A Knight Without Armor has a very audible bonus. Tucked away inside the back cover is a Johnny Western CD,  which includes not one the Paladin theme, but the only commercial recording Richard Boone ever made (he narrates to music).

which includes not one the Paladin theme, but the only commercial recording Richard Boone ever made (he narrates to music).

“A soldier of fortune was the man called Paladin,” and that goes for Richard Boone.

∞∞∞∞∞

Grade: B-plus

Winsor McCay left us animated Gertie the Dinosaur, surreal comics

(NOTE: The following feature was originally published in The Kansas City Kansan on June 2, 2000.)

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

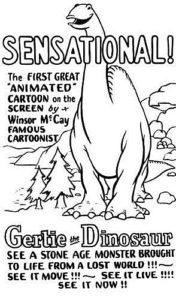

It all began with Gertie.

Gertie, the very first movie dinosaur, has evolved through various The Lost World and One Million B.C. remakes and variations, stomping on in Fantasia, The Land Before Time, and sundry animated features including Spielberg’s Jurassic Park pair. Now, Dinosaur lumbers in. Opening weekend take for the Disney animated feature tallied almost $40 million. Is there a pterodactyl in the house?

Dinosaur, in its seemingly 3-dimensional surroundings, stuns. It raises the bar once again for computerized art, something that Gertie’s creator, Winsor McCay, would have appreciated. All he had were pencil and ink 91 years ago.

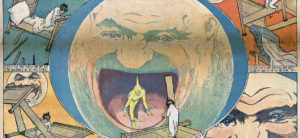

McCay did not create his Gertie at the very beginning of his career; first there were his comic strips featuring wildly surreal characters and plots. Born in 1869 at Spring Lake, Michigan, McCay always loved drawing. Never formally schooled (a grade school dropout), he moved to Chicago at 17, drawing posters for a meager living. McCay grabbed any art lessons he could. He later designed murals in Cincinnati for a local museum. McCay also drew for various local newspapers.

His comic strip career was launched in 1903 after newspaper mogul James Gordon Bennett learned of McCay’s talents. The fledgling artist was contracted as a strip artist on The New York Evening Telegram. Under the pseudonym “Silas,” McCay created several strips, the most remembered being Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend, in 1904. The dream angle was carried on in various ways throughout his career. An argument could be made, in fact, that Gertie could be construed as a dream-like trip back in time.

His comic strip career was launched in 1903 after newspaper mogul James Gordon Bennett learned of McCay’s talents. The fledgling artist was contracted as a strip artist on The New York Evening Telegram. Under the pseudonym “Silas,” McCay created several strips, the most remembered being Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend, in 1904. The dream angle was carried on in various ways throughout his career. An argument could be made, in fact, that Gertie could be construed as a dream-like trip back in time.

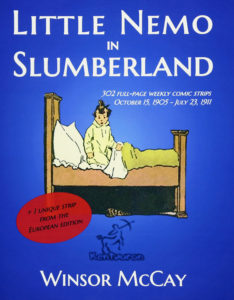

The real turn in McCay’s career, however, came in 1905 after he created Little Nemo in Slumberland. Using his real name now, McCay drew with surreal abandon. Each strip episode focused  on the imaginative dreams experienced

on the imaginative dreams experienced

nightly by little boy Nemo as his bed elevated, alternately zooming and floating through the cosmos and never-never-lands. McCay’s Nemo world was a shadowless one of distorted dimensions. Characters included Impy the Cannibal, Flip the Dwarf and Morpheus, the King of Slumberland.

Would this strip be ahead of its time now, almost a century later? The late and wonderfully great Calvin and Hobbes strip comes to mind as the nearest to Little Nemo that anyone has come.

Gertie, the silent and friendly Brontosaurus, stomped onto the scene four years later, while Nemo was continuing its national syndication. At this time, McCay had begun a parallel career dabbling in the infant art of animation. He created animated versions of Little Nemo in Slumberland and experimented with a fascination of his, the dinosaur. Realize that in those silent film days, each individual cell was photographed one frame at a time. And each cell, drawn on paper  then, had to be hand drawn separately. That meant McCay and his assistants had to create some 3,000 separate drawings by hand for a typical three-minute film. (Silent speed was 18 frames per second.)

then, had to be hand drawn separately. That meant McCay and his assistants had to create some 3,000 separate drawings by hand for a typical three-minute film. (Silent speed was 18 frames per second.)

Nonetheless it was worth it for McCay and the history of animation. Gertie was a sensation, spewing numerous other Gertie cartoons. Plot lines were similar. In the original, actually named Gertie the Trained Dinosaurus, a flat plained area near a water line is shown as Gertie ambles from the distance to screen front. Gertie then stares at the screen, no doubt amazing 1909 audiences. (These films were shown in vaudeville houses and at trade meetings.) Gertie moves her neck from screen left to right, still staring and seemingly smiling. She witnesses a tug of war between a sea monster and a woolly mammoth. The monster has latched onto the hairy elephant’s long trunk. As Gertie watches, a small monkey crawls on Gertie’s back, sliding up and down her neck. Finally, Gertie grabs the pest and, after winding up  her long neck, tosses the monkey into oblivion.

her long neck, tosses the monkey into oblivion.

A cartoon version of McCay then appears walking from right screen front. Dressed in a tuxedo, he takes a bow, presumably for the creation we have just witnessed. Gertie picks him up by his collar and politely puts him back off screen. Then Gertie sits back, lifts her huge right leg, and waves at the audience. The End.

But that is not all. During public exhibitions of this movie, as well as his other Gertie flicks, a live McCay would stand beside the screen and interact with Gertie. At one point in one of the films, McCay would throw an actual ball to Gertie, which she would then seem to catch via animation. (McCay would throw it to an assistant behind the screen.)  The showmanship was an awesome, magical blend of the live and the animated.

The showmanship was an awesome, magical blend of the live and the animated.

At one point in his vaudeville career, McCay and Gertie shared the bill with W. C. Fields and Houdini. McCay’s influential career on stage, celluloid and paper flourished until his death in 1934.

His epitaph: “Simply, I could not keep myself from drawing.”

FILM VIGNETTES and ASIDES ∞∞ Part 1 ∞∞

By Steve Crum

•ACE IN THE HOLE (1951): The first time I saw it, I regretted not having seen it decades earlier. I would have shown it to my high school journalism students as part of their ethical training. But alas, I was retired from teaching. Billy Wilder’s jarring movie about an exploitive, corrupt journalist (Kirk Douglas) still teaches all of us.

•ACE IN THE HOLE (1951): The first time I saw it, I regretted not having seen it decades earlier. I would have shown it to my high school journalism students as part of their ethical training. But alas, I was retired from teaching. Billy Wilder’s jarring movie about an exploitive, corrupt journalist (Kirk Douglas) still teaches all of us.

•THE ADVENTURES OF MARK TWAIN (1944): After first viewing this majestic  biographical movie during my grade school years on our Philco TV, I was struck by the incredible acting of Frederic March in the title role. Max Steiner’s classic score continues to stay with me. Then there is the concluding scene of Twain-Clemens dying in bed while Halley’s Comet darts across the night sky. Sam Clemens, you see, was born the last time the comet was seen, 74 years to the day. Amazing.

biographical movie during my grade school years on our Philco TV, I was struck by the incredible acting of Frederic March in the title role. Max Steiner’s classic score continues to stay with me. Then there is the concluding scene of Twain-Clemens dying in bed while Halley’s Comet darts across the night sky. Sam Clemens, you see, was born the last time the comet was seen, 74 years to the day. Amazing.

•THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD (1938): Perfect storytelling, if for  nothing else than the Technicolor, Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s music, the brilliant set pieces, the actors, and even the specifically recorded sound of arrows rocketing to their targets. Heroism vs tyrants has never been told better.

nothing else than the Technicolor, Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s music, the brilliant set pieces, the actors, and even the specifically recorded sound of arrows rocketing to their targets. Heroism vs tyrants has never been told better.

•THE AFRICAN QUEEN (1951): It was the leeches that imprinted on my 4 year-old mind when  my parents and I first saw this movie. I think it was at a drive-in. I probably fell asleep before it all ended, but when Bogart had Hepburn help him peel one leech at a time from his body…what a slithering memory.

my parents and I first saw this movie. I think it was at a drive-in. I probably fell asleep before it all ended, but when Bogart had Hepburn help him peel one leech at a time from his body…what a slithering memory.

•AIRPLANE! (1980): I do so love puns, and this picture is chock full. Shirley you also love the non-stop parody and sight gags running rampant.

•AIRPORT (1970): Alfred Newman’s thematic music underscores this all-star, mainly airborne soaper. I loved its soundtrack so much I bought the German version (different cover art) when I was stationed in the Army near Kaiserslautern in 1971.

•ALEXANDER’S RAGTIME BAND (1938): It has all those Irving Berlin songs sung by Merman, Faye, and Ameche…but what lingers most is a socko song and dance routine by Wally Vernon, “This Is the Life.” He was thereafter sadly underused as a lame sidekick in B-westerns.

•ALEXANDER’S RAGTIME BAND (1938): It has all those Irving Berlin songs sung by Merman, Faye, and Ameche…but what lingers most is a socko song and dance routine by Wally Vernon, “This Is the Life.” He was thereafter sadly underused as a lame sidekick in B-westerns.

•ALIEN (1979): First seeing this terrifying classic sci-fi/horror movie with my younger sister is fixed in memory. The thing is, my sister Becky was 29 years old in 1979. I invited her to an evening screening, and neither of us knew the terrors awaiting. Realize that Becky loathes scary movies because…they really scare her. And Alien really scared me too. The combination of suspense and graphic violence still shocks.

•ALIEN (1979): First seeing this terrifying classic sci-fi/horror movie with my younger sister is fixed in memory. The thing is, my sister Becky was 29 years old in 1979. I invited her to an evening screening, and neither of us knew the terrors awaiting. Realize that Becky loathes scary movies because…they really scare her. And Alien really scared me too. The combination of suspense and graphic violence still shocks.

•ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN (1976): This wonderful film about truth and courage was released at a good time since I was just beginning my journalism teaching career. The landmark movie was inspiring to me and my students. No doubt it had much to do with increasing class sizes in j-classes nationwide.

Nightmarish imagery, great acting highlight horror that persists in ‘The Lighthouse’

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

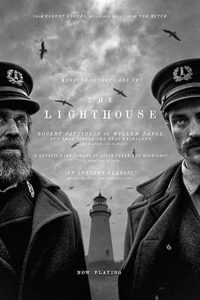

After spending 109 minutes watching The Lighthouse, the film’s message persists: “It’s bad luck to kill a seabird!” I so believe it now, as it is uttered early in the movie by Thomas Wake (Willem Dafoe). Wake’s warning to Robert Pattinson’s Ephraim Winslow tragically goes unheeded.

Directed and co-written by Robert Eggers (along with co-writer/brother Max), The Lighthouse is a highly original but grim motion picture on several levels. This psychological horror drama, released last October, is jammed with nightmarish imagery and tour de force acting (Dafoe and Pattinson are its only two actors). Both actors perform awesomely.

Besides the actors, there are enough auditory devices to fill several films. I speak of surround sound effects such as seagulls, heavy rain, and the damned foghorn that nearly affected me as much as it does the pitiful Winslow character. Both he and Wake are lighthouse keepers, arriving at the story’s opening to replace two others we see departing. The job calls for four weeks tending the remote lighthouse, whereupon they will be replaced. It is telling that neither duo says anything to the other as they pass by. Not even a nod or gesture.

Once settled in, it becomes clear these two are total strangers who now have to work together for a month. The emphasis here is the “strange” in strangers. Dafoe’s older, bearded Wake immediately takes charge as sole keeper of the lighthouse, while delegating all menial labor chores to Pattinson’s Winslow. To make it worse, his hard work is repeatedly criticized by his new boss. Wake repeatedly orders that the floor scrubbing be done over and over. He is rarely satisfied with the results. It does not take long before Winslow revolts at his slave labor treatment.

Once settled in, it becomes clear these two are total strangers who now have to work together for a month. The emphasis here is the “strange” in strangers. Dafoe’s older, bearded Wake immediately takes charge as sole keeper of the lighthouse, while delegating all menial labor chores to Pattinson’s Winslow. To make it worse, his hard work is repeatedly criticized by his new boss. Wake repeatedly orders that the floor scrubbing be done over and over. He is rarely satisfied with the results. It does not take long before Winslow revolts at his slave labor treatment.

Four months into their job, Winslow is still not permitted to even step into the beacon tier of the lighthouse. Wake keeps it locked tight.

All this said, and without divulging more plot development, things hit the proverbial fan when their relief ship fails to show up with replacements. By that time, their booze-filled world of isolation is compounded by a terroristic seagull, bloody water, and a scary mermaid.

All this said, and without divulging more plot development, things hit the proverbial fan when their relief ship fails to show up with replacements. By that time, their booze-filled world of isolation is compounded by a terroristic seagull, bloody water, and a scary mermaid.

This study in paranoia, terror and insanity is somewhat adapted from the unfinished short story, The Light-House, by Edgar Allen Poe.

Mention must be made that it was shot in gorgeous black-and-white, enhancing the atmosphere. And it is not in widescreen. Realizing the movie is set in the late 19th Century, let us hope the pandemic quarantine we are all going through now never results in what occurs in The Lighthouse.

![]() Plaudits to Jarin Blaschke’s stunning cinematography, which was Oscar nominated earlier this year.

Plaudits to Jarin Blaschke’s stunning cinematography, which was Oscar nominated earlier this year.

The wild finale brought to mind three classic films: Kiss Me Deadly (1955), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and The Birds (1963). See The Lighthouse to believe it.

=====

GRADE, On A to F Scale: A-