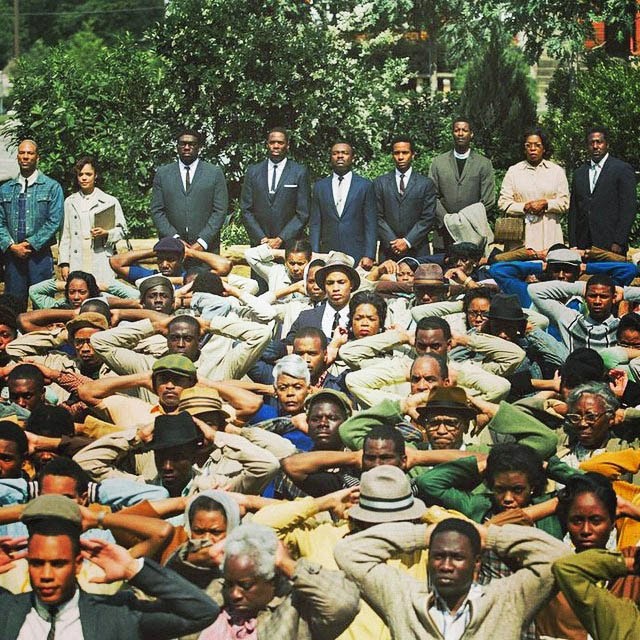

Selma is a powerful dramatization of events that occurred between white supremacists and voting rights African-Americans led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., among others, in 1965. Recreations of brutalities perpetrated by Selma, Alabama police and many of its citizens upon unarmed civil rights marchers and demonstrators are unsettling and brutally graphic.

In the process of chronicling those transitional, too often grim days following The Civil Rights Act of 1964, director Ava DuVernay and screenwriter Paul Webb have Hollywoodized the story to the extent of depicting President Lyndon Johnson as an obstructionist to the African-American cause. Nonetheless, Selma is compelling cinema. Opening with King’s 1964 acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, a tragic event in Birmingham, Alabama is then shown: the murder of four youngsters in a Sunday morning church bombing. (That terrorist act actually occurred in 1963.)

In the process of chronicling those transitional, too often grim days following The Civil Rights Act of 1964, director Ava DuVernay and screenwriter Paul Webb have Hollywoodized the story to the extent of depicting President Lyndon Johnson as an obstructionist to the African-American cause. Nonetheless, Selma is compelling cinema. Opening with King’s 1964 acceptance of the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, a tragic event in Birmingham, Alabama is then shown: the murder of four youngsters in a Sunday morning church bombing. (That terrorist act actually occurred in 1963.)  Cut then to Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey) as she attempts again to register to vote in the Selma courthouse. Once again, she is thwarted by ridiculous regulations like having to recite each of Alabama’s 67 county judges. Faced with a requirement not required for the white population, she leaves defeated and unable to vote. Jump to Dr. King (David Oyelowo in a superb performance) meeting with President John (Tom Wilkinson) at the White House. “We want the right to vote,” King says to LBJ’s noncommittal ears. “This administration will just have to set that (voting rights) aside,” Johnson retorts. According to the film, LBJ later meets with FBI Director J. Edgar Hooever to nullify any voting agitation stirred by King and his followers. Wire tapping King in his bedroom is Hoover’s method of choice.

Cut then to Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey) as she attempts again to register to vote in the Selma courthouse. Once again, she is thwarted by ridiculous regulations like having to recite each of Alabama’s 67 county judges. Faced with a requirement not required for the white population, she leaves defeated and unable to vote. Jump to Dr. King (David Oyelowo in a superb performance) meeting with President John (Tom Wilkinson) at the White House. “We want the right to vote,” King says to LBJ’s noncommittal ears. “This administration will just have to set that (voting rights) aside,” Johnson retorts. According to the film, LBJ later meets with FBI Director J. Edgar Hooever to nullify any voting agitation stirred by King and his followers. Wire tapping King in his bedroom is Hoover’s method of choice.

As Alabama’s Governor George Wallace (Tim Roth) consults with his henchmen, as well as President Johnson, about how to physically deal with Dr. King, meticulously planned, peaceful protests resume. The culmination of that event was the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. incidentally, the movie was filmed in various George and Alabama locations, including the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where the Bloody Sunday assault by Selma police actually occurred.

While Selma serves as a heartfelt tribute to the memory of Dr. King, it also documents events that shaped our nation.

Technically, DuVernay uses, maybe overuses, shadows in many closeups of King. Since Oyelowo is not an exact match for King, maybe this was a wise choice.

Technically, DuVernay uses, maybe overuses, shadows in many closeups of King. Since Oyelowo is not an exact match for King, maybe this was a wise choice.

Pluses extend to Carmen Ejogo as Coretta Scott King and Bradford Young’s cinematography.

However, the minuses center on a couple of miscasts and a few historical flaws. Why Tom Wilkinson and Tim Roth were cast as Southerners is a puzzlement, particularly since neither physically resemble their characters (LBJ and George Wallace). Neither do they exude the necessary fervor nor speak with believable accents.

Frankly, knowing they are both British got in my way. OK, so Oyelowo is also British, but he is a virtual unknown. Of course his celebrity is now forever changed.

Throughout the film, I was shocked to see LBJ portrayed as such a racist obstructionist to the Civil Rights Movement. Later I commented to a screening rep that I had no idea Johnson used the n-word when he was president (referencing King and his followers), that he pushed Hoover into wiretapping King, and that he repeatedly refused to compromise in regard to the Voting Rights Act.

Throughout the film, I was shocked to see LBJ portrayed as such a racist obstructionist to the Civil Rights Movement. Later I commented to a screening rep that I had no idea Johnson used the n-word when he was president (referencing King and his followers), that he pushed Hoover into wiretapping King, and that he repeatedly refused to compromise in regard to the Voting Rights Act. As it turns out, my suspicions were not entirely warranted since there are White House-taped conversations in which Johnson used such racist language. I was shocked to discover (and hear) such after seeing Selma. In order to paint a story picture of good versus evil, even President Johnson had to appear as one of the bad guys.

Referring to the relationship between King and Johnson, Mark Updegrove, Director of the LBJ Presidential Library, recently said, “They were very much supportive of each other.” Rep. John Lewis, portrayed in Selma by Stephan James, agrees with Updegrove, but dismisses the criticism as “unfair.” Both he and DuVernay consider the Johnson depiction as nothing more than poetic license for the sake of an even better story.

“I wasn’t interested in making a white-savior movie,” DuVernay boldly asserts. In other words, the devil with Lyndon Johnson.

“I wasn’t interested in making a white-savior movie,” DuVernay boldly asserts. In other words, the devil with Lyndon Johnson.

With that skewed objective, she should have renamed the movie King.

—————————

GRADE on A to F Scale: A-