By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

Gus, Jolson’s black butler persona, continued the one-upmanship of his “superiors” in the Shuberts’ Winter Garden hit of 1913, “The Honeymoon Express.” Jolie sang “My Yellow Jacket Girl,” “The Spaniard That Blighted My Life,” “You Made Me Love You,” “He’d Have To Get Under–Get Out and Get Under,” and “Who Paid the Rent for Mrs. Rip Van Winkle,” among other popular tunes.

After its initial New York run, Feb. 6-June 14, 1913, the show played a grueling, 40-city schedule cross country (and out of country), Sept. 18, 1913-March 30, 1914, from Atlantic City to Toronto to Los Angeles. It was truly a Valentine for Kansas City when Jolie and “The Honeymoon Express” company performed for two weeks, Feb. 1-14, 1914.

After its initial New York run, Feb. 6-June 14, 1913, the show played a grueling, 40-city schedule cross country (and out of country), Sept. 18, 1913-March 30, 1914, from Atlantic City to Toronto to Los Angeles. It was truly a Valentine for Kansas City when Jolie and “The Honeymoon Express” company performed for two weeks, Feb. 1-14, 1914.

———-

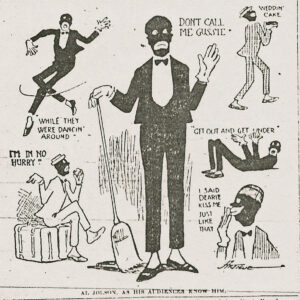

The caricature collage (by an unknown artist) of Jolson is particularly fascinating, since it depicts six impressions of

the 1914 Al Jolson stage persona. The work is entitled: AL JOLSON, AS HIS AUDIENCES KNOW HIM.

the 1914 Al Jolson stage persona. The work is entitled: AL JOLSON, AS HIS AUDIENCES KNOW HIM.

The February 4, 1914 Interview with Jolson (no byline); includes a great one panel comic art w/six caricatures of Jolson in blackface, captioned AL JOLSON AS HIS AUDIENCES KNOW HIM.

———-

Here, to make it much easier to read, is the entire transcribed, lengthy interview with Jolie by a Kansas City Star reporter covering the theatrical event. It is fascinating.

AL JOLSON, WORKINGMAN

———-

The Comedian Says He’s The Laborer You Read About

———

Some Day, He Is Going to Retire to a Farm Where He Will Only Have to Work Like a Horse

———

He says himself that they are beginning to call him old Al Jolson. He’ll be 30 in a few more years.

But that’s the penalty of doing the black face in these musical comedy days when the fabled wealth of …lnd would not pay for the new kind of clothes a show must dress in. Black cork is so inexpensive that everybody associates it with the crude days of the past, before managers discovered that all a show needed was clothes and talcum powder.

Hence, old Al Jolson, who’ll be 30 after awhile.

FARM WORK AS A REST CURE

Jolson’s smashing success in cork seems to call attention to a somewhat ancient truth that has been more or less lost sight of recently. Which is (it was in the old copy books) that all you have to do to succeed is to work at it. Jolson works at it. He works like a longshoreman. Prodigal of voice, of energy, of good nature, he meets every demand of applauding audience until the last curtain, and then while the people whom has kept laughing for two hours are discussing at after theater suppers the easy life he leads, he is writhing under the hands of an osteopath kneading the soreness out of his throat muscles.

“Six more years of it,” says Jolson, speaking out of the cloths wrapped round his throat, “then back to the farm, where I’ll only have to work as hard as the horses.”

The farm–it’s a ranch really–is just outside Oakland and there Jolson and his wife plan to spend their declining days when Al gets to be 35.

THE WORKINGMAN YOU READ ABOUT

“A farm and a million is supposed to be the ambition of everybody on the stage,” says Jolson. “I’ve got the farm and don’t intend to wait for the million. I quit at 35 without counting the roll. Meanwhile anybody who wants to know what work is like can come and watch me. I’m the workingman you read about in books.”

Jolson has been a workingman since back in ’98 when he began to do the blackface thing in a circus–or in the stay-for-the-concert-only-ten-cents that followed the show in the big top. He was 13 then. Previously he had been playing marbles on the streets of Washington with woolly headed negro boys and acquiring their dialect, and incidentally their marbles. From the circus to minstrelsy, thence to vaudeville and finally to stardom in musical comedy have been rapid steps. You see, he was working all the time. Merely that. Few people have tried that method before.

NO LOAFING BETWEEN VERSES

When Jolson isn’t singing or dancing, he’s making a speech. He doesn’t like to be idle. Frequently he has as much as a minute and a lot of seconds between songs, in which he has absolutely nothing to do. So he makes the audience a speech. Audiences, being foolish and liking nothing better than to laugh, got to look upon these speeches as part of the program. They got to demanding them. It just goes to show what a lot of work a man can make for himself when he is so simple as to go out and look for it.

But Jolson’s first speech wasn’t to an audience. It was to a manager. It was one of the most successful speeches he ever made. It was in the days when his novel plan of working all the time had just begun to get results. He was beginning to be known. A manager looked him up and offered him a contract. Jolson wasn’t sure at that time that he wanted to continue in blackface. He was feeling so independent about it that he made up his mind he wouldn’t take a contract except at a figure that would make it worth his while. He determined to name a price the manager would refuse. So he made his speech

AL THOUGHT TWICE–QUICKLY

He said he wasn’t stuck on the stage anyway. He said he rather thought he’d quit and go into business. He said it was a hard life, audiences were fickle, hotels were poor, Pullman berths were hot. He said he was a young man with many opportunities before him and felt he ought to think twice before taking a contract that probably would mean, in the end, that he would have to follow the stage all his life.

“So I’ll just make you this proposition,” said Jolson. “I’ll sign up at $1,000 a week. Take it or leave it.”

“I’ll give you $75,” said the manager.

“Done,” said Jolson.

Thus, all unwillingly, was Al Jolson dragged into the career now his.

#

Please note that below one of the display ads for “The Honeymoon Express,” “Ben-Hur” is again being presented, except this time it is following Jolson’s show at the Sam S. Shubert Theater. In 1908, when Dockstader’s Minstrels were in town, “Ben-Hur” was showing at another theater. Like Jolson, “Ben-Hur” obviously had proverbial legs.

°°°°°°°°°°

NEXT: PART 6, “DANCING AROUND”….