(NOTE: The following feature was originally published in The Kansas City Kansan on June 2, 2000.)

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

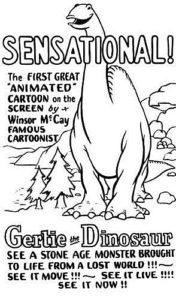

It all began with Gertie.

Gertie, the very first movie dinosaur, has evolved through various The Lost World and One Million B.C. remakes and variations, stomping on in Fantasia, The Land Before Time, and sundry animated features including Spielberg’s Jurassic Park pair. Now, Dinosaur lumbers in. Opening weekend take for the Disney animated feature tallied almost $40 million. Is there a pterodactyl in the house?

Dinosaur, in its seemingly 3-dimensional surroundings, stuns. It raises the bar once again for computerized art, something that Gertie’s creator, Winsor McCay, would have appreciated. All he had were pencil and ink 91 years ago.

McCay did not create his Gertie at the very beginning of his career; first there were his comic strips featuring wildly surreal characters and plots. Born in 1869 at Spring Lake, Michigan, McCay always loved drawing. Never formally schooled (a grade school dropout), he moved to Chicago at 17, drawing posters for a meager living. McCay grabbed any art lessons he could. He later designed murals in Cincinnati for a local museum. McCay also drew for various local newspapers.

His comic strip career was launched in 1903 after newspaper mogul James Gordon Bennett learned of McCay’s talents. The fledgling artist was contracted as a strip artist on The New York Evening Telegram. Under the pseudonym “Silas,” McCay created several strips, the most remembered being Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend, in 1904. The dream angle was carried on in various ways throughout his career. An argument could be made, in fact, that Gertie could be construed as a dream-like trip back in time.

His comic strip career was launched in 1903 after newspaper mogul James Gordon Bennett learned of McCay’s talents. The fledgling artist was contracted as a strip artist on The New York Evening Telegram. Under the pseudonym “Silas,” McCay created several strips, the most remembered being Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend, in 1904. The dream angle was carried on in various ways throughout his career. An argument could be made, in fact, that Gertie could be construed as a dream-like trip back in time.

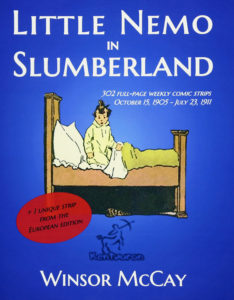

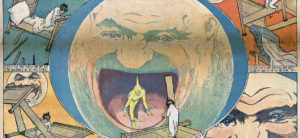

The real turn in McCay’s career, however, came in 1905 after he created Little Nemo in Slumberland. Using his real name now, McCay drew with surreal abandon. Each strip episode focused  on the imaginative dreams experienced

on the imaginative dreams experienced

nightly by little boy Nemo as his bed elevated, alternately zooming and floating through the cosmos and never-never-lands. McCay’s Nemo world was a shadowless one of distorted dimensions. Characters included Impy the Cannibal, Flip the Dwarf and Morpheus, the King of Slumberland.

Would this strip be ahead of its time now, almost a century later? The late and wonderfully great Calvin and Hobbes strip comes to mind as the nearest to Little Nemo that anyone has come.

Gertie, the silent and friendly Brontosaurus, stomped onto the scene four years later, while Nemo was continuing its national syndication. At this time, McCay had begun a parallel career dabbling in the infant art of animation. He created animated versions of Little Nemo in Slumberland and experimented with a fascination of his, the dinosaur. Realize that in those silent film days, each individual cell was photographed one frame at a time. And each cell, drawn on paper  then, had to be hand drawn separately. That meant McCay and his assistants had to create some 3,000 separate drawings by hand for a typical three-minute film. (Silent speed was 18 frames per second.)

then, had to be hand drawn separately. That meant McCay and his assistants had to create some 3,000 separate drawings by hand for a typical three-minute film. (Silent speed was 18 frames per second.)

Nonetheless it was worth it for McCay and the history of animation. Gertie was a sensation, spewing numerous other Gertie cartoons. Plot lines were similar. In the original, actually named Gertie the Trained Dinosaurus, a flat plained area near a water line is shown as Gertie ambles from the distance to screen front. Gertie then stares at the screen, no doubt amazing 1909 audiences. (These films were shown in vaudeville houses and at trade meetings.) Gertie moves her neck from screen left to right, still staring and seemingly smiling. She witnesses a tug of war between a sea monster and a woolly mammoth. The monster has latched onto the hairy elephant’s long trunk. As Gertie watches, a small monkey crawls on Gertie’s back, sliding up and down her neck. Finally, Gertie grabs the pest and, after winding up  her long neck, tosses the monkey into oblivion.

her long neck, tosses the monkey into oblivion.

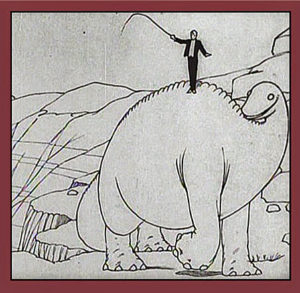

A cartoon version of McCay then appears walking from right screen front. Dressed in a tuxedo, he takes a bow, presumably for the creation we have just witnessed. Gertie picks him up by his collar and politely puts him back off screen. Then Gertie sits back, lifts her huge right leg, and waves at the audience. The End.

But that is not all. During public exhibitions of this movie, as well as his other Gertie flicks, a live McCay would stand beside the screen and interact with Gertie. At one point in one of the films, McCay would throw an actual ball to Gertie, which she would then seem to catch via animation. (McCay would throw it to an assistant behind the screen.)  The showmanship was an awesome, magical blend of the live and the animated.

The showmanship was an awesome, magical blend of the live and the animated.

At one point in his vaudeville career, McCay and Gertie shared the bill with W. C. Fields and Houdini. McCay’s influential career on stage, celluloid and paper flourished until his death in 1934.

His epitaph: “Simply, I could not keep myself from drawing.”