My review of the newly released VHS version of Dracula was published in The Kansas City Kansan (Crum on Film) on Oct. 29, 1999. This was during the pre-DVD era.

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

Has one of the masterpieces of horror cinema been trashed? For almost 70 years Tod Browning’s Dracula has been viewed and re-viewed in reissued and restored versions. In fact, last year Universal Pictures sent pristine digitalized prints of the Bela Lugo vehicle around the country for even more viewings.

Dracula was one of six Universal horror greats showcased. Kansas City’s Tivoli Theater exhibited the films locally.

Dracula looked good. Unfortunately, seven decades of storage and wear have grated even the master prints. Age spots, jumps, and wrinkled frame lines are visible even after Universal’s latest face-lifting. But director Browning’s tried and true vampire tale, probably seen by this writer 30 or 40 times, still  elicited the quiet chill and creepiness of old. I emphasize “quiet” because, believe it or not, 1931’s Dracula was made without a musical score. When Lugosi greets Jonathon Harker on those eerie, winding, cobwebbed stairs, there is no crescendo of musical notes, no violin screeching in slow pull.

elicited the quiet chill and creepiness of old. I emphasize “quiet” because, believe it or not, 1931’s Dracula was made without a musical score. When Lugosi greets Jonathon Harker on those eerie, winding, cobwebbed stairs, there is no crescendo of musical notes, no violin screeching in slow pull.

Last month that all changed. A newly composed recorded stereo musical soundtrack has been added to video versions of Dracula, and some fans and critics are irate at the blasphemy of altering an American original. Keep the original as Browning intended, some say, and let our imaginations fill in emotional notes. The outrage is not as internees as when ted Turner began coloring black and white movies (a procedure that he has long since stopped doing—thank goodness), but there is a definite vocal minority of protesters.

Let it be added that Universal is still selling a newly restored video version of Dracula without any musical score—just like grandpa always liked.

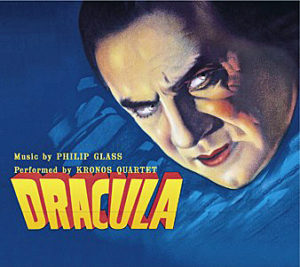

As for yours truly, the new musical score written by Philip Glass and performed by the Kronos Quartet, is admittedly hard to accept. Trying to keep an open mind and ear, I settled back in my surround sound living room, eased into La-Z-Boy City, and absorbed the new Drac. The internationally heralded Kronos Quartet does a superb job with the Glass score. But there are two problems inherent.

As for yours truly, the new musical score written by Philip Glass and performed by the Kronos Quartet, is admittedly hard to accept. Trying to keep an open mind and ear, I settled back in my surround sound living room, eased into La-Z-Boy City, and absorbed the new Drac. The internationally heralded Kronos Quartet does a superb job with the Glass score. But there are two problems inherent.

PROBLEM 1: As in most films, the music accentuates and/or underscores action and character emotion. In Dracula, the audience has relied on the “less being more” theory throughout. When Lugosi’s Count Dracula enters or leaves a room, the silence itself can be blood curdling. The vampire as vapor wisps in and out, under and around. Giving the walking dead man a chamber music cue is distracting. It certainly robs the viewer of one’s inner, much more effective cue device.

PROBLEM 2: Especially noticeable in a four-speaker set-up, Dracula’s score is clearly divided into the rear speakers. Dialogue is segregated to the front speakers. Make sure you sit more toward the front speakers to nearly understand the speech since separation is not balanced. The music dominates, and actors’ words are often lost in the chords. I often had to rewind the VCR, lean forward, and re-listen to a line.

PROBLEM 2: Especially noticeable in a four-speaker set-up, Dracula’s score is clearly divided into the rear speakers. Dialogue is segregated to the front speakers. Make sure you sit more toward the front speakers to nearly understand the speech since separation is not balanced. The music dominates, and actors’ words are often lost in the chords. I often had to rewind the VCR, lean forward, and re-listen to a line.

But then again, the music is quite atmospheric, very listenable and inventive. I would have preferred a full orchestra with a Jerry Goldsmith or Bernard Herrmann brush, but Glass and Kronos are acceptable. At least give Universal credit for investing in a noble idea and having the gumption to alter one of its landmark films.

Dracula, 1931 original unscored version: A-minus. Dracula, 1931 with added score: C-plus.