By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

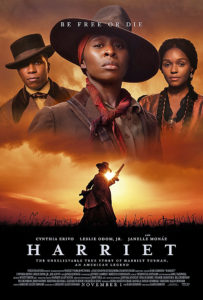

The central character in the biographical Harriet is Araminta “Minty” Ross (1822-1913), far better known then and today as Harriet Tubman. She is extraordinary, this movie far less so. And that is a shame, since Tubman’s exploits deserve more than just a mostly dry telling. For example, the 125 minutes certainly adhere to the facts of her enslavement since birth in Maryland, followed by her escape north to safety in Philadelphia, and then repeatedly returning (13 times) to her Maryland roots to free relatives and friends.

However, it is unfortunate that director/co-screenwriter Kasi Lemmons (Talk to Me) fails to give Harriet and her story anything more than a one-dimensional treatment. The film looks and feels more like a well done History Channel reenactment. The facts are solid, but the emotional impact is lacking.

The story itself (co-written by Lemmons and Gregory Allen Howard—based on his story) focuses on Harriet (Cynthia Erivo) when she is in her early 20s, and living as a slave on a plantation in Dorchester County, Maryland. She falls in love with and marries John Tubman (Zackary Momoh), who is enslaved at the same location. When the stern “master” plans to sell her to another slave owner, she immediately makes plans to escape, and then travel north via an “underground railroad” to the free state of Pennsylvania. Through drive and good luck, Harriet eludes her owner’s tracking dogs and posse.

Noteworthy is the fact that Harriet’s faith in God is demonstrated throughout her escape. Even with bloodhounds baying in the near distance, Harriet would often drop to her knees  in the forrest, and engage in prayer—asking for guidance in deciding which way to run for safety. The film portrays this as trance-like behavior. God would tell her to either go right or left, according to the movie.

in the forrest, and engage in prayer—asking for guidance in deciding which way to run for safety. The film portrays this as trance-like behavior. God would tell her to either go right or left, according to the movie.

This is a good time to interject that when Tubman was a child, she suffered a severe head injury when an overseer threw a heavy weight at another slave, hitting her instead. Harriet later said, “It broke my skull.” Historical accounts report that Tubman had painful headaches and seizures the rest of her life.

All this might be due to her bouts of dropping to pray at various stressful times in her life, occurrences that Tubman attributed to hearing God’s call. Incidentally, the film references her injury (though not in detail), and infers it affected her anti-slavery actions for the rest of her life. This is because Tubman herself thought her head pains guided her on the righteous path to free slaves by God.

Once with anti-slavers in Philadelphia, Tubman is aided by William Still (Leslie Odom Jr.), an abolitionist/writer. He is so inspirational that Harriet decides to return to her Southern homestead to rescue her husband and bring him back to Philly. He has remarried, thinking Harriet was surely dead. Then he refuses to go with her. Harriet finds others to rescue (like her parents and siblings), a trek repeated over a dozen times.

Once with anti-slavers in Philadelphia, Tubman is aided by William Still (Leslie Odom Jr.), an abolitionist/writer. He is so inspirational that Harriet decides to return to her Southern homestead to rescue her husband and bring him back to Philly. He has remarried, thinking Harriet was surely dead. Then he refuses to go with her. Harriet finds others to rescue (like her parents and siblings), a trek repeated over a dozen times.

Note: The movie indicates that Harriet changed her first name from Araminta after meeting Still. In fact, she changed it to Harriet soon after marrying John. It is no big historical deal, really. Just chalk it up to poetic license.

In Philadelphia, Harriet befriends Marie Buchanon (Janelle Monáe), a boarding house proprietor.

In Philadelphia, Harriet befriends Marie Buchanon (Janelle Monáe), a boarding house proprietor.

Harriet’s ongoing rescues ratchet up the intensity to capture her. Her former owner, Gideon Brodess (Joe Alwyn) employs professional slave catchers to tighten the search. It soon becomes a deadly match between Tubman and Brodess, which occupies about 3/4 of the film’s running time. It was during this period that Harriet was appropriately nicknamed “Moses.”

There is a brief narrated scene toward the finale which depicts “Moses” leading an armed assault during the Civil War, in which 750 slaves were rescued. Yes, Harriet always carried a loaded pistol, and used it when necessary. Omitted from the screenplay is Tubman’s memorable anti-slavery work with abolitionist John Brown. (That would have made a movie unto itself.)

There is a brief narrated scene toward the finale which depicts “Moses” leading an armed assault during the Civil War, in which 750 slaves were rescued. Yes, Harriet always carried a loaded pistol, and used it when necessary. Omitted from the screenplay is Tubman’s memorable anti-slavery work with abolitionist John Brown. (That would have made a movie unto itself.)

There were many other valiant episodes in Harriet Tubman’s life unmentioned in Harriet, but it would take a mini-series or 5-hour movie to cover it all. That said, the Harriet Tubman story would have fared better as a Ken Burns documentary than as a Kasi Lemmons fictional biography.

Then again, with the former we would be missing some fine work by Cynthia Erivo.

=====

GRADE, On A to F Scale: C+