My deadlines + newsprint began 70 years ago

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

THROWING BACK to 1954, when 7 year-old Stephen Crum began his journey/destiny of journalism. In my 61st & Ann Avenue home in KCK, I loved reading The Kansas City Times and Star (both the morning and evening editions). So I published my own newspaper, really a one-pager, The Ann  Avenue News. Since I had no typewriter or copy machine, it was a laborious task. Every story was hand written by me…and included my single panel comic, Sammy Shoe. (It featured a dorky kid with huge feet.) I churned out maybe six copies of the same issue each week, and hand delivered them to a like number of neighbors. The stories were brief and gossipy. This enterprise lasted two issues.

Avenue News. Since I had no typewriter or copy machine, it was a laborious task. Every story was hand written by me…and included my single panel comic, Sammy Shoe. (It featured a dorky kid with huge feet.) I churned out maybe six copies of the same issue each week, and hand delivered them to a like number of neighbors. The stories were brief and gossipy. This enterprise lasted two issues.

My journalistic spirit rekindled big time when I was a junior and senior at Wyandotte High School. As a member of the Pantograph newspaper staff, I drew cartoons, took photos, and wrote news and features. Thirty-five years later, I was teaching journalism at Wyandotte, and advising the Pantograph.

In between, I became associate editor of The Bulletin student newspaper at Emporia State (then Kansas State Teachers College). I also wrote news and features (play reviews, etc.), and drew cartoons.

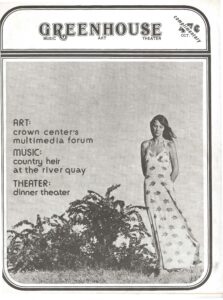

After my stint in the Army, I briefly wrote for an arts and entertainment magazine, Greenhouse, distributed throughout Greater Kansas City. That was 1974.

I surprised myself when I researched the number of high school newspapers I advised over the years following college. They include: Rosedale High School’s The Rosedalian, Harmon’s The Talon, Washington’s The Washingtonian, Schlagle’s Diachron, Wyandotte’s Pantograph, and Bishop Ward’s Outburst.

I surprised myself when I researched the number of high school newspapers I advised over the years following college. They include: Rosedale High School’s The Rosedalian, Harmon’s The Talon, Washington’s The Washingtonian, Schlagle’s Diachron, Wyandotte’s Pantograph, and Bishop Ward’s Outburst.

In the midst of all the writing, teaching and deadlines, I proudly served as President of the Kansas Scholastic Press Association, 1985-87.

In the midst of all the writing, teaching and deadlines, I proudly served as President of the Kansas Scholastic Press Association, 1985-87.

Factor in three city newspapers for which I wrote film and stage reviews and interviews, and drew cartoons: The Kansas City Kansan, The Wyandotte West, and Courier Tribune (Kansas City Missouri’s Northland).

_____

Sadly, few local newspapers still publish. The Internet rules.

Sadly, few local newspapers still publish. The Internet rules.

I miss those deadlines..sort of. I miss being able to actually hold a paper copy of one’s publication. I miss feeling the pride and accomplishment on distribution day.

Remembering the forgotten GREENHOUSE magazine…

By Steve Crum

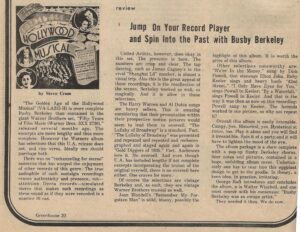

By Steve Crum THROWING BACK to 1974, when I wrote a smattering number of reviews for GREENHOUSE, a 28-page monthly arts and entertainment magazine distributed throughout Greater Kansas City. It was The Pitch of its day, per se.

THROWING BACK to 1974, when I wrote a smattering number of reviews for GREENHOUSE, a 28-page monthly arts and entertainment magazine distributed throughout Greater Kansas City. It was The Pitch of its day, per se. Greenhouse is among the 14 newspapers and magazines in my life that I either wrote for or advised/edited. Yes, I bleed printer’s ink.

Greenhouse is among the 14 newspapers and magazines in my life that I either wrote for or advised/edited. Yes, I bleed printer’s ink.Recollections of 1960s entertainers…

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum I was dazzled by: director/producer Tyrone Guthrie, “Man of La Mancha,” “Hello, Dolly!” (Dorothy Lamour), Hans Conried (“Absence of a Cello”), Kenny Rogers and The First Edition, Pat Paulsen, Skitch Henderson, Stan Kenton, Nancy

I was dazzled by: director/producer Tyrone Guthrie, “Man of La Mancha,” “Hello, Dolly!” (Dorothy Lamour), Hans Conried (“Absence of a Cello”), Kenny Rogers and The First Edition, Pat Paulsen, Skitch Henderson, Stan Kenton, Nancy  Wilson, The Amazing Kreskin, Mitch Miller, Preservation Hall (from New Orleans), Glenn Yarbrough, Pete Fountain, The Back Porch Majority, Sandy

Wilson, The Amazing Kreskin, Mitch Miller, Preservation Hall (from New Orleans), Glenn Yarbrough, Pete Fountain, The Back Porch Majority, Sandy  Baron, The Ramsey Lewis Trio, Mantovani and His Orchestra, Drew Pearson, Robert Russell Bennett, William Stafford (Kansas poet; my guest teacher for a session), and the touring musical “Half a Sixpence.”

Baron, The Ramsey Lewis Trio, Mantovani and His Orchestra, Drew Pearson, Robert Russell Bennett, William Stafford (Kansas poet; my guest teacher for a session), and the touring musical “Half a Sixpence.”Aptly titled ‘The End’ focuses on dark side living

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

The film title The End references the apocalyptic end of the world. Joshua Oppenheimer (director/producer/screenwriter) has taken that grim premise to unfamiliar territory, fashioning it into 149 minutes of a family musical-drama-tragedy.

It is not easy to watch.

Co-screenscribes Oppenheimer and Rasmus Heisterberg set their tale two decades following an environmental disaster that has wiped  out most of the world. A wealthy family live in a relatively luxurious bunker (more like a mini-house) located within the confines of a cavelike salt mine. Among the group are Mother (Tilda Swinton), Father (Michael Shannon) and Son (George MacKay). Living in nearby rooms are the family’s butler (Tim McInnerny), doctor (Lennie James), and friends Mary (Danielle Ryan) and Bronagh Gallager (no character name).

out most of the world. A wealthy family live in a relatively luxurious bunker (more like a mini-house) located within the confines of a cavelike salt mine. Among the group are Mother (Tilda Swinton), Father (Michael Shannon) and Son (George MacKay). Living in nearby rooms are the family’s butler (Tim McInnerny), doctor (Lennie James), and friends Mary (Danielle Ryan) and Bronagh Gallager (no character name).

The group tries to maintain a semblance of normal daily life, including physical exercises (they have a swimming pool), doctor checks (he also dispenses drugs), shared mealtimes, reading books, writing journals, and art collecting. (We assume they had access to a museum?) Oddly, they conduct safety drills.

Individually, the soft spoken characters have quirks and nuances they still try to either hide or downplay after 20 years together. The real focus in this regard is on the son’s lack of sophistication about love and sex. His parents’ relationship is devoid of any display of affection, even in private. The boy’s lack of role modeling is challenged following the discovery of a wounded girl (Moses Ingram) in the outer cave. Their burgeoning relationship becomes the crux of the plot and hope for the future.

Individually, the soft spoken characters have quirks and nuances they still try to either hide or downplay after 20 years together. The real focus in this regard is on the son’s lack of sophistication about love and sex. His parents’ relationship is devoid of any display of affection, even in private. The boy’s lack of role modeling is challenged following the discovery of a wounded girl (Moses Ingram) in the outer cave. Their burgeoning relationship becomes the crux of the plot and hope for the future.

Note that at any given time, a character will burst into song and dance. Rename “burst” as speaking in rhyme—with full orchestral accompaniment. It is not even at Rex Harrison level of sing-talk. There are 13 such “songs” with titles like “A Wonderful Gift,” “We Kept Our Distance” and  “The Mirror.” The latter tune is embellished by impressive camera work reminiscent of Orson Welles.

“The Mirror.” The latter tune is embellished by impressive camera work reminiscent of Orson Welles.

Overall, the sadly courageous group seems to suffer from PTSD via boredom and fear. Such is understandable. Laughs are a rarity in The End. I kept thinking about Debbie Downer from SNL.

If Tilda Swinton speaking a sorrowful lyric like “each day is like the last” entertains you, The End might be your tea cup.

—————

GRADE on an A-F Scale: C-

Psychic world explored in fascinating documentary ‘Look Into My Eyes’

By Steve Crum

By Steve Crum

There are surprises and revelations in Look Into My Eyes. But the quirky documentary about psychics has a couple of unanswered questions. Maybe we need a psychic to figure it all out?

No crystal balls are used, but there are candles, dimly lit rooms and theatrics. Produced and directed by Lana Wilson, who has created four other documentaries, Look Into My Eyes is a fascinating glimpse into the life of a professional psychic. Make that seven psychics operating in New York City. The 108 minutes suggest they all function in their apartments—either in the same building or in close proximation.

There is a scene, however, in which a psychic solicits readings outdoors.

There is a scene, however, in which a psychic solicits readings outdoors.

The people seeking the mediums are troubled and obsessed in communicating. If you are like me, curious about the monetary payment for each meeting, stay wanting. Fees are not mentioned on camera. It must be substantial since the psychics do not seem to have another job. (By the way, the apartments are anything but elaborate.)

The central figures are not “fortune tellers.” These mediums share messages from departed spouses, friends, family members, and even pets.  They tap into the the outer world of the deceased, and elicit both joy and tears.

They tap into the the outer world of the deceased, and elicit both joy and tears.

We witness the actual seance, the psychic’s connection with the client, the answered and unanswered questions, and tearful impacts. It seems real. Perhaps the most jarring exchange occurs when a client wants to know if his birth mother regrets having given him up when born. We  can all empathize.

can all empathize.

Is everything we see in Look Into My Eyes true? Are we witnessing reality? My question is an ongoing one in our world of reality TV. For example, we know that a program like the super popular Survivor is unscripted, but it is all taped by several cameras. Participants realize they are on camera, even in supposed private conversations. Maybe everyone has learned to ignore a camera constantly focused on them. So goes the Eyes documentary. How can the psychic and client truthfully interact with one or two cameras obviously in the room?

Half of Look Into My Eyes is devoted to the private lives of the psychics themselves, sans clientele. What makes a guy or gal become a  psychic? Do they have anything in common with other psychics? (The seven regularly meet with each other in a therapy session to share common concerns, both professional and private.) One of the group is also shown at singing lessons. (He has a long way to go.)

psychic? Do they have anything in common with other psychics? (The seven regularly meet with each other in a therapy session to share common concerns, both professional and private.) One of the group is also shown at singing lessons. (He has a long way to go.)

These messengers are fraught with their own problems, insecurities, and histories. Yet they are driven to answer strangers’ queries due to their ability to connect.

Director Lana Wilson captures the isolationism of the psyche as it plays out in Hannah Buck’s spot on editing. The film is reminiscent of the style of documentarian Frederick Wiseman, and that is great praise.

—————

GRADE on an A-F Scale: A-